A few days ago, I was talking with my friend and colleague Alessio Assonitis, the Senior Director of the Medici Archive. The Archive offers a range of paleography learning experiences. Paleography, of course, is the study and transcription of handwritten historical documents.

Before the invention of the printing press in 1440, everything was written by hand, including entire books. One medieval scribe, describing the physical labor of writing all day, notes how “it mists the eyes, it curves the back, it breaks the belly and the ribs, it fills the kidneys with pain, and the body with all kinds of suffering.” He continues by asking the reader to keep their fingers off the page because “just as a hailstorm ruins the fecundity of the soil, so the sloppy reader destroys both the book and the writing. For as the last port is sweet to the sailor, so the last line to the scribe.”1

It was not easy to write for a living during the Middle Ages! With age, one’s writing style often changes. This could be a pivotal career moment for a medieval scribe, as a legible hand was a prerequisite. Sometimes, however, an individual might consciously and deliberately change their writing style. During our conversation, Alessio pointed out that that was the case with Michelangelo, one of history’s greatest artists. Michelangelo’s writing style underwent significant change over the course of his life. Indeed, that change was so great that Alessio now teaches a course on how to read Michelangelo’s “multiple” hands.

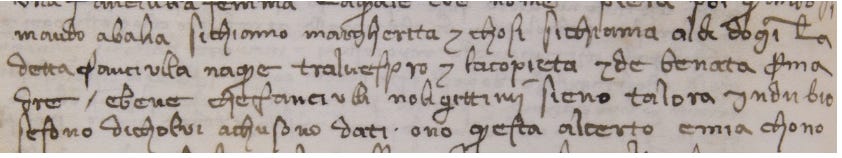

Early in his career, Michelangelo wrote in a mercantile script. Mercantile, or mercantesca as professional paleographers call it, was a script that emerged in Tuscany, specifically Florence. As its name suggests, mercantesca was the script of Florentine merchants, bankers, and traders. It therefore comes as no surprise that Michelangelo first wrote in this style. A generic example of mercantile script is pictured below, followed by one of Michelangelo’s autographed sonnets from 1497.

However, as Michelangelo’s exposure to Renaissance Humanism grew, he made a conscious decision at some point to adopt a humanistic cursive script called cancellaresca. Scholars now believe that the great artist made this decision between 1497 and 1502. Unlike its business-minded counterpart, humanist script developed in a restricted and culturally élite Florentine environment. It was the official script of Tuscany’s diplomats, chancelleries, courts, and emerging literati. For Michelangelo, the new calligraphy must have felt like an upgrade, a move from business to first class. Once again, an example is shown, followed by a letter written by Michelangelo in 1518.

To learn more about Michelangelo’s hand, Robert Tallaksen’s dissertation, The Influence of Humanism on the Handwriting of Michelangelo Buonarroti, presents the history and motivating factors behind this fascinating story.

So far, we’ve focused on Michelangelo’s handwriting. But where does AI enter the picture? I’m glad you asked. Researchers have recently developed models that can read handwritten documents line-by-line and transcribe them into plain text. This has been a research bottleneck for many years. Professional historians can spend years honing their paleographic (transcription) skills. These skills are typically narrow in scope, restricted to a specific period (Mercantile script of the Renaissance) or the handwriting of a particular historical figure (Lincoln).

Existing AI models from companies like Transkribus are just as narrow, if not more so, in their scope. That is, models can read a single kind of script from a specific period. In the case of Michelangelo, best practice right now is to train two models, one on his earlier mercantile style, a second on his later humanist style. A single model, capable of reading both, would be even better. That is probably within the realm of possibility, given today’s technology. However, things get a bit more interesting when we add hundreds, even thousands, of hands to the mix. We must remember that thousands of scribes and merchants were working in Italy at that time. They may have shared a common calligraphy, but each had a distinctive writing hand. That variability is a challenge. For example, could we train a single model to read any document written in Mercantile script, no matter the author or the writing quality?

Technically speaking, the paleography challenge calls for a form of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) rather than narrow AI. AGI is the way the human mind works. It’s a multi-purpose tool, capable of handling a range of tasks. Narrow AI, on the other hand, performs exceptionally well on a single task. Many models often outperform humans when the task is specific, like reading a particular script from a narrow sliver of time. Yet a narrow AI approach leads to the creation of hundreds, possibly thousands, of models. That’s because we need a model for each unique hand/script. This is unsustainable, especially when, as my friend Alessio notes, the Medici Archive features a million different writing styles. An AGI solution appears to be the answer, thanks to the artistic hand of one of the world’s greatest artists. Thanks Michelangelo!

Raymond Clemens & Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (Ithaca, NY, Cornell University Press, 2007) p. 23.