Tinker Toys and Research Creativity

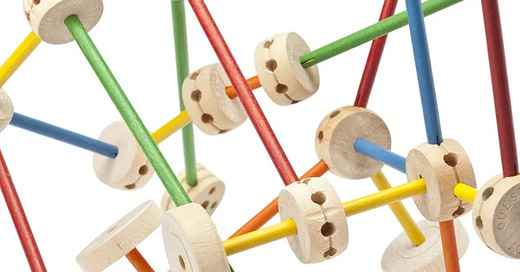

When I was a young child – even before I met my first Lego block – I can remember playing with Tinker Toys. One can create all kinds of interesting things with Tinker Toys. One such structure is pictured above.

The two basic blocks in a Tinker Toy set are the wheel and the dowel. Each wheel has precision holes drilled in it, allowing the child to insert dowels (the connectors) into it. The process is then repeated, resulting in a web of connections between the wheels. All kinds of interesting objects can be created this way. Steve Jobs once quipped that “creativity is just connecting things.” If that’s true, this is creativity at its most basic, even if the linked objects are physical rather than mental.

Tinker Toy structures, then, could be considered a physical representation of the creative process. Let’s unpack that thought just a bit. If we imagine the wheels as concepts or ideas, then the length of the dowels between them would represent their mental proximity. Some concepts lie at a distance from each other. Jacob Soll, for example, makes a connection between accounting and the fall of nation-states. His creative and compelling analysis reveals that even the most distant and unlikely connections are possible if made correctly. Accounting and economic history, on the other hand, are much closer together. Hence, conceptual links between these two fields are less surprising.

Let’s take our Tinker Toy analogy one step further and ask, “At what point does the length of the dowel – the distance between two concepts – become so great that the intellectual structure collapses? Or is there a limit? Questions like these are not easily answered, though we can probably state with a certain degree of confidence that the farther the distance, the greater the risk. Much depends on the norms that bind a community of research practice together.

Edward De Bono, a leading thinker in the field of creative thinking and innovation, approaches creativity as connectivity from a different angle. According to De Bono, there are but two kinds of thinking – vertical and lateral. Vertical thinkers take a logical, step-by-step approach, hewing closely to established patterns and accepted methods. In contrast, lateral thinkers make conceptual leaps that others might shy away from. They seek creative and indirect solutions to problems by approaching them from new and unexpected directions. Interestingly, most creativity scholars do not use De Bono’s terms, preferring instead the words convergent or divergent to describe these two ways of thinking.

De Bono maintains that lateral thinking is the more creative of the two as it breaks free from traditional thinking patterns and challenges existing assumptions. That is, it signals out-of-the-box thinking. Lateral thinking, though, comes with a much higher level of risk as the distance between concepts is much farther. The foregoing discussion suggests a three-tiered model of research risk.

Scholars who play it safe typically adhere to a limited set of discipline-approved connections and research norms, preferring the stability of vertical or convergent thinking. Others, though, make connections to ideas or concepts farther afield. The creative zone is where that happens. And finally, some like to seek out concepts and ideas in disciplines far removed from the one they’re working in. This strategy is riskier than the other two as convincing peers that seemingly unrelated ideas belong together can be challenging.

With Tinker Toys, the connector dowels are cut to pre-specified lengths. The child doesn’t have to worry if the wooden wheels are too far or too close to each other. That all changes when we grow up. Adults live and work in scholarly communities where research norms and structures matter. In such communities, there are limits. Not just any idea can be connected to any other idea. The length of the dowel – the distance between the wheels or concepts – only stretches so far. 1

My friend Mike Benveniste shared this three-tiered model of research risk with me in a conversation a couple weeks back. I want to thank him for his ongoing generosity.